By Martin Waleczek, DFN-CERT

Having an online existence has never been more rewarding. Almost daily someone wins the million dollar jackpot of a lottery and wants to share it with you, you get links to the best prices at the local pharmacy or online stock exchange and your IT department or bank kindly reminds you to change your expired password by clicking on a complicated link (again), that has been shortened for your convenience. Everyone wants to help you. But do they really?

Phishing is the act of sending out millions of identical promises to unsuspecting online users and working hard to monetise the few actual responses. With this approach to social engineering, victims are nudged to handing out sensitive personal information like login passwords or financial data freely by means of official looking web forms or even lured into providing access to sensitive resources of company networks by elaborate psychological manipulation.

The phishing experience usually starts with a more or less suspicious email that contains a link to an external website or an unsolicited attachment. The phishing campaign itself may have started weeks or even months before when the attacker made the decision about which peer group, industry, company or person should be their next target. Such decisions are conscious ones and one has to keep in mind, that phishing campaigns don’t just happen. Someone decided to harvest someone else’s personal data or use their computing resources for their own personal gain.

First contact

The effort put into those campaigns can vary widely. Since there are pre-constructed phishing kits available, everyone with access to some kilobytes of webspace and the ability to send promotional emails can set up their own landing page and collect credentials with relative ease. But reaching specific user groups or aiming at high-profile accounts of targeted associations requires significant reconnaissance in order to customise the campaign accordingly.

The various breaches and data leaks of the recent years provide attackers with billions of valid email addresses (i. e. possible recipients) for their first contact. There are datasets for specific industries sold or even publicly available in the darker corners of the web. So whenever a new pandemic shows up the attacker can just grab their folder of contacts in health care, start a new campaign and hope that at least some users are overwhelmed with the recent developments and thereby neglect their online hygiene long enough for the attacker to get their foot in the door.

The same event can be utilised for a campaign targeting users unacquainted with the new videoconferencing solution or online tool that their employer would like them to use in order to work from home. As could be expected, the COVID-19 pandemic brought several such campaigns with it. Fake notifications for missed online meetings were among those attempts targeting users while establishing their home-offices.

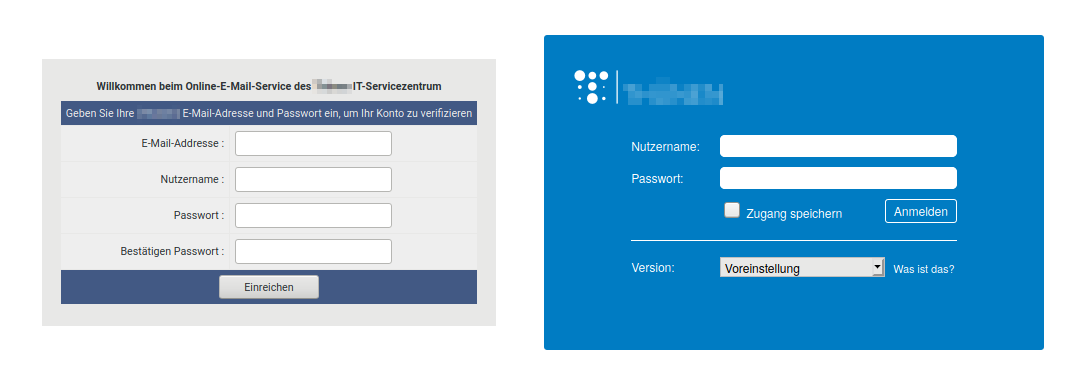

For the first contact, attackers will take advantage of any social, cultural or environmental development that presents itself and see how much human curiosity or sense of duty can be exploited. Most of the time the campaigns aren’t even highly current, but just slightly adapted to the target audience. If some user falls for the email in their inbox that tells them to reset their password in an online form or log in to the company’s new online portal with their current credentials, the campaign’s first milestone, the first contact, is reached. The link provided in the email leads to a spoofed webpage that resembles the expected log-in page well enough not to raise any suspicion. The slick design of common web portals like the standard login pages of the Outlook Web App, Dropbox or Paypal certainly helps here.

Some campaigns just stop after the first contact. There is not much harm done and the harvested credentials will find their way to some shady database and may end up being sold as part of a collection that is used as a precursor for more advanced phishing or malspam campaigns that require credible sender addresses. Harvested financial data such as bank account or credit card details may be sold individually and is only rarely used by the attacker themselves.

Customised campaigns

Some threat actors use more sophisticated emails and web pages for their phishing campaigns. In the academic environment there is often a multitude of login pages for different services offered by parts of the institution: imagine libraries, e-learning platforms, content management systems (CMS) and various other services. For a targeted campaign the attacker will check the existing environment and adapt the campaign content. Looking for students’ credentials? Your quota is full. Interested in administrative contacts for the CMS? You didn’t change your password in years. Looking for research papers? A fellow scientist asks, if you have access to a paper in their field that you can reach by clicking a (specially prepared) link to your own library.

The success of targeted campaigns relies on not raising suspicion (unspecific campaigns just rely on mass mailing and statistics). The member of a university that does not heavily use Microsoft’s products is not likely to fall for a fake Outlook Web App landing page, so the campaign is adapted accordingly. Speaking the local language helps as well as providing a local sender address, e. g. of the local IT department.

Email addresses (more specifically the ‘From:’ part of the email header) can often be easily spoofed since the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) does not require the checks necessary to identify spoofed addresses by default. If spoofing protections are in place, the attacker can use an address from a familiar institution instead. Today’s scientific operations rely on interdisciplinary as well as cross-university projects, and communication among scientists across borders is encouraged, so an incoming request from another scientist will rarely raise suspicions at a first glance.

The boldest attackers will try to use the local infrastructure to stay under the radar. If the first contact campaign or a breach yields valid email or user credentials, those can be used to send even more convincing emails, look for additional targets in connected online address books or even use the content of past emails in a new campaign disguised as a follow up on the earlier conversation.

The content of the email aims at convincing the reader to click on a provided link. Consequently, the matter has to be relevant to the recipient, which may require additional reconnaissance regarding the local e-learning platform, CMS or whichever service is most promising. For example, e-Learning platforms tend to send notifications to upcoming events, a CMS might provide weekly or monthly statistics and, as a fallback, every postmaster will warn their users in case their mailbox is reaching capacity.

If the attacker’s email seems plausible in general there is one last obstacle for the attacker: the URL for the fake log-in page. Due to the combined effort of security researchers and browser vendors users are getting better at recognising fraudulent URLs, so some hint to the institution or some recognisable keywords (webmail, library, ..) are expected by the attentive user.

Again there are different levels of sophistication when constructing those URLs. Registering full domains for this purpose is rarely an option, since this involves the submission of personal details most of the time and is quite expensive for a campaign that only runs for some days. There is a plethora of services that offer the registration of free subdomains for little or no money, so often the domains of companies like weebly.com or 000webhost.com show up in phishing campaigns, prefixed by almost non-random subdomains like ‘portalit00’, ‘itservdesksuprt’ or ‘mailboxstoragenotifynode645’. All of which were part of recent campaigns targeting universities.

If those subdomains are not convincing enough, more sophisticated campaigns will use the long or short form of the name of target institutions as a subdomain. Those URLs are frequently used in campaigns where a non-standard log-in form is expected by the user, for example because of a target university’s special corporate identity. The special log-in page of the target can be rebuilt by skilled web programmers or simply saved to a single file with an appropriate browser extension. There is only little programming knowledge necessary to be able to direct entered credentials to a local text file or database, which can be collected later. Often the user is redirected to the expected log-in page later and sometimes even logged in automatically with the credentials initially provided.

With HTTPS usage passing 90% last year and the padlock in browsers’ address bars becoming synonymous for online security there is an optional icing on the campaign cake: a decent campaign needs a valid certificate for the subdomain used. This has been a problem in the past when the authorities responsible for signing those digital certificates made their fortune, but has become far less of a hassle with the advent of free X.509 certificates for Transport Layer Security (TLS) in recent years. The attacker can just register an arbitrary subdomain at a free hoster and create a fitting certificate with the help of Let’s Encrypt’s free service in less than a minute. Let’s Encrypt issued their billionth certificate in February 2020.

Recently a group known for targeting the academic sector even started using some target’s infrastructure for the construction of non-suspicious links. Some universities offer services like URL shorteners for their constituency, so the campaign went ahead and just used those short URLs with a trustworthy domain to hide and redirect to their own just a little less trustworthy subdomains of free hosters, thereby avoiding most email filters looking for suspicious URLs. The campaign even used the names of real people working at different universities as senders, so that a quick online search for the person might just lead to the conclusion that there is an individual who used to work at university X and now works at my institution in IT and just wants to tell me that my mailbox is full. What a nice person. The link looks fine. I click.

Help!

Nowadays even sophisticated phishing campaigns with authentic landing pages and convincing stories can be set up easily by attackers with different motivations and varying technical background. There are phishing kits readily available that can be customised to a specific target if needed and even trained professionals can have trouble identifying sophisticated scams.

But the international CERT community has its own arsenal when it comes to identifying new threats and countering the attackers’ efforts. New phishing campaigns are often identified by automatic analysis of incoming emails and the information is shared rapidly among the CERTS of National Research and Education Networks (NRENs) around the globe so that local action can be triggered almost instantly.

This includes the identification, and if necessary, the deactivation of compromised accounts in order to stop ongoing campaigns, but it starts beforehand with extensive training of the user base. It is vital to raise awareness to the techniques used in malicious campaigns and help the average user to identify suspicious activity. Users are encouraged to report such events even after the act of submitting personal data, clicking on links or opening attachments. No professional will ever blame You for reporting Your own mishaps, because every bit of information helps to fight the larger threat.

Unfortunately, the actors behind established campaigns know their cat-and-mouse game quite well and will happily switch to the next compromised user account in line, if the one used for the current batch of phishing emails is shut down. So identifying a campaign before it speeds up is key.

This is why NRENs monitor content storing websites (pastebins) and forums in the darker parts of the web for published user credentials. Every such data point can act as a precursor for a new phishing campaign, so account owners are notified and urged to change their password when their email address shows up in a new collection of usernames and passwords. There is a lot to be gained by the simple act of using a password manager to store unique passwords for each service used. On the one hand, this avoids techniques such as credential stuffing, where a malicious actor takes a collection of credentials and feeds those to a third-party internet service. Users who tend to reuse their passwords will just end up having multiple compromised accounts with different services. On the other hand, once a password unique to a certain service shows up in a collection of credentials in the dark web, this is a strong indicator, that the service has been compromised. This information can help other users of the service to protect their data before it is misused by a malicious third party.

Monitoring can help identifying new phishing campaigns at earlier stages. Since tailored subdomains are used for targeted campaigns, analysts can deploy tools like urlscan.io to identify newly registered subdomains of typical keywords and wildcards (think ‘uni\*.weebly.com’) in the scan engine. Similarly, the Certificate Transparency Log (CTL) can be used to identify newly issued certificates for subdomains that suspiciously resemble possible phishing targets. Great effort is placed into the identification of those candidate domains and information is shared freely among the community by those who identify future threats in order to enable the affected parties to file their take-down notice with their respective hosters. Most of those hosters respond quickly to requests like this and active campaigns can be stopped timely.

Help us!

Unfortunately, all these efforts won’t prevent your inbox from receiving phishing mails daily, but this knowledge might support you in identifying online scams. There is a very basic set of rules that should be honoured:

- Don’t click on links in emails.

- Don’t open unsolicited attachments.

That’s it, you’re safe now. Most of the phishing scams today involve malicious attachments, since harvesting, revising and reselling personal data requires so much more time and effort than just waiting for someone to open an attachment and setting up an electronic wallet to collect ransom for the soon to be encrypted files. Actually, there is a whole industry now offering ransomware-as-a-service including software development and even tech support for victims who have trouble using cryptocurrencies, because it just works so well. Don’t open unsolicited attachments.

Links in emails are harder to ignore since we are used to the streamlined processes of online shops or services that start with a single click on an offer or friendly reminder in your mail or webmail client. If the events after the click closely match your expectations of what should happen, your safeguards are

lowered and maybe not every visited URL will be checked to the last character. In some browsers the address bar will show the domain only instead of the full address of the visited page, which is considered a security feature, but really hampers the quick identification of sophisticated fraud. Visit log-in pages from bookmarks. Don’t click on links in emails.

If you still do click on the link and enter your login data and shortly after recognise that a mistake was made, stay calm and try to contain the damage. Go to the website in question directly, log in with the now compromised credentials if still possible and change them immediately.

And please share your experience with your local peers and security contacts. They may be able to help you stay on top of the events and your mishap may be the reason why the new sophisticated phishing campaign stops before it really gains momentum.

About the author

Martin Waleczek is an experimental physicist by training and joined the Incident Response Team (IRT) of the CERT of the German National and Education Research Network (DFN-CERT) in early 2016. In his role as a security consultant, he focuses on writing security advisories for upcoming threats and vulnerabilities as well as handling incidents and their aftermath.

Read more on the GÉANT Cyber Security Month 2020: https://connect.geant.org/csm2020