By Nil Ortiz, Carolina Fernández, Jordi Guijarro and Shuaib Siddiqui, i2CAT

Knowing about our public identity

Our identity is scattered along a myriad of sites on the Internet: public bodies, banking, social networks… As in real life, tracking what we have and keeping some order to it is key to deciding how to make the most of it. Data is no different: it is essential to know what we own, where it is, how it is used and how to manage it. After all, data represents also our identity.

The first step is tracking our digital presence on the Internet: who is exposing which data from us? We can identify such data (from us or everyone else) in search engines, which allow advanced filtering parameters or “dorks” via the web [1] or command-line [2]. We could restrict the search with specific indicators (e.g. specific site, dates, type of files) to understand how we could be profiled. It is useful to restrict by i) name and activity (social networks, work, academy, etc); ii) email; or even iii) a legal identification number. The public existence of this data (specially the one which is personal, or even worse, sensitive) can point to a data breach and warn about the potential impersonation we could be subject to (e.g., with a legal identification number).

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) tools can help automating the retrieval of data, starting from small bits of information and correlating against multiple domains; as well as growing this data. Sometimes, profiling – via tools such as “theHarvester”- can obtain enough data so as to attempt taking economic advantage through targeted scams (CEO fraud, identity theft) or general ones (phishing). Besides, our digital traces and preferences can also be used by social networks and portals to prioritise or filter specific content; by organisation’s competence to infer internal information; during recruitment processes to double-check references, skills or simply to contact us to sell products. Tools like “email2phonenumber” or haveibeenpwned.com allow us to find whether data like our phone or email are public, while others can correlate data for us.

Handling which data we share

Now, how did this data get published? While it is sometimes indexed from other websites without our consent, most of the time it is a product of what we share on platforms or services. In the latter case we should review which online accounts we own (for instance looking for registration messages in our email inbox) and take some time to review the security and privacy settings to further secure access to our account and to adjust the amount of information we want to share with the service.

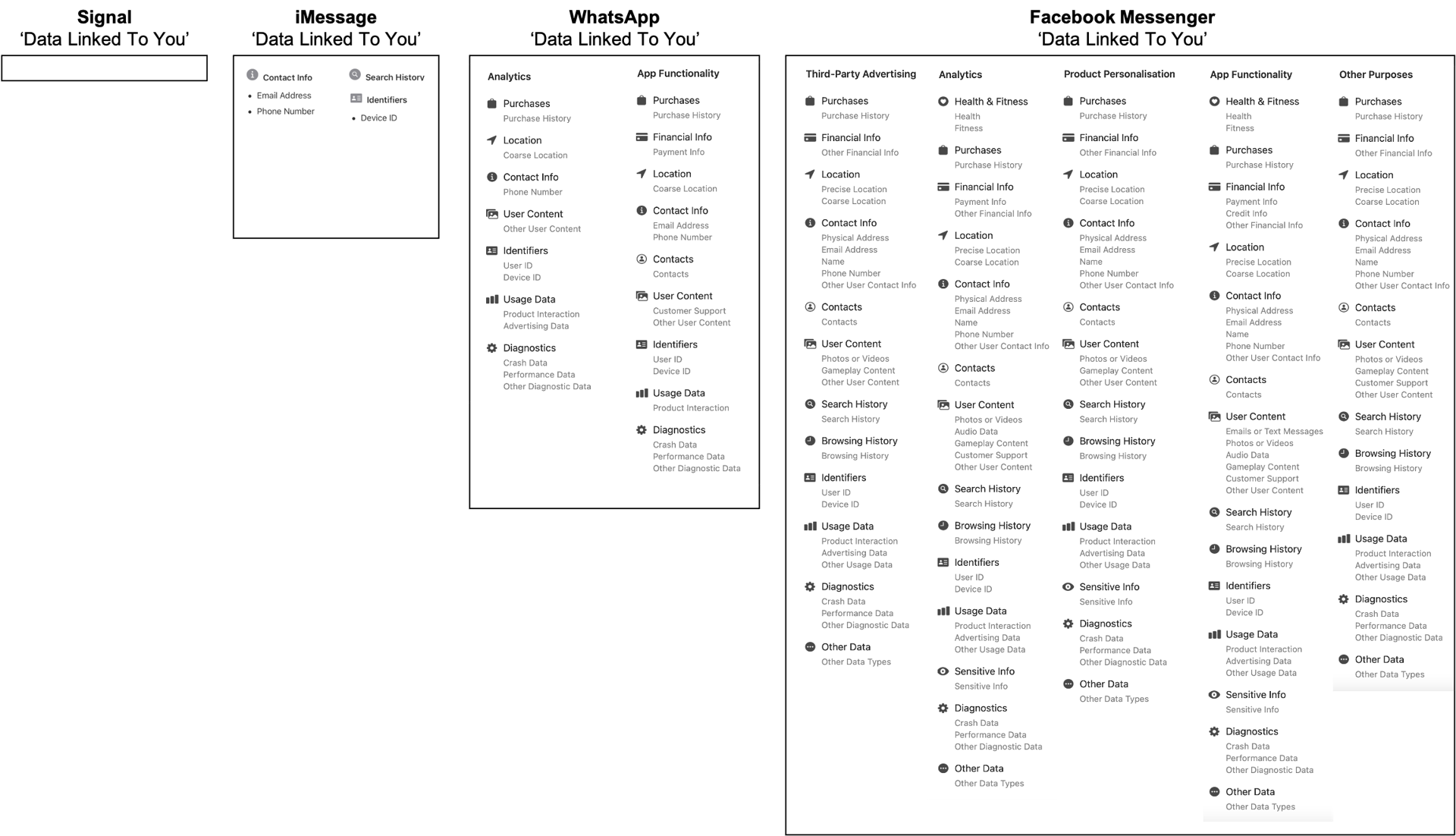

In GDPR there is a principle named “data minimisation”, which states that those using personal data should keep it to the minimum required for the needs of the given service. As users we should review how our data is used and what for; then discern if we are requested to provide more than what we consider necessary for the service. For instance, a service may ask (optionally) for both a telephone and an email, but we may not want to receive calls on our personal phone. In this case we could pick one of them and either provide a secondary phone number or an alternate or alias account email where spam or attacks are less disrupting. Naturally, as long as data is optional we can also minimise what we provide, contact the organisation for justification on such processing (if not stated in their data privacy terms), or in the worst case, consider not using the service at all. An example of an apparently excessive amount of data retrieved/linked to the user in order to provide a service can be observed in some services of the following image: where all provide asynchronous messaging, some perform an elaborate user profile of the user.

Image source

A user has, among others, rights on its own data in order to:

- Know which of its data is being used and for which purposes

- Rectify inaccurate data

- Delete it, or

- Restrict how it is used.

These rights co-exist with the right of the organisations to use the data. In some circumstances, these rights are not directly offered in account management. If so, we may contact the Data Protection Officer (DPO) of the given organisation. In case of lack of response or not complying with the request after due time, we may need to contact our national Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) to process a formal complaint.

Minimising impact of data breaches

Besides reducing the data we share, one of the best ways to stay safe is to stay vigilant. Being aware of the incidents and security breaches that happen around the world is very important: just as we keep track of regular issues reported on the news, even when those may not directly affect our life, we should do the same with cybersecurity incidents. If wildfires or heavy storms are increasing in neighbouring countries, common sense indicates that we should start to prepare for similar situations in our area. Similarly, if we see an increase in a certain type of attacks or a new vulnerability being exploited, we should look into how that could affect us. A very good exercise is to try to put ourselves in the position of the victim: what would we do if our organisation had a ransomware incident and all our work personal data was sold to competitors or became public domain? Would we have to start from scratch or would we have some backup plan [3] to minimise the impact of the incident? Could someone gather enough information to perform a behaviour and identity profile about us to perform advanced attacks against us or impersonate us against third parties? These are some of the questions which we should ask ourselves when we see others being impacted by cybersecurity incidents ─ so we can adopt measures to be more resilient when the storm arrives.

When we find ourselves as a victim of a data breach, we should have two key questions in mind: i) how does this affect me, and ii) how does this affect my organisation. Depending on the leaked information, it could be a minor nuisance for you and or your organisation, or a major problem.

One of the most important things to keep in mind is that anyone can become a victim of a data breach ─ even security professionals. We should not try to hide it or be embarrassed. Being transparent and contacting the IT team or company behind the breached application should be a priority, since they will indicate which actions to take and what is the degree of impact of the incident. When reaching out to these security professionals, it is important to make it easy for them to understand and assess what happened; so we should provide:

- A comprehensive story of what happened

- How did we learn of the incident

- What actions did we take already (if any), and

- What kind of information we think might have been compromised.

Giving them as many details as we can will likely reduce their response time and impact. It is also a good idea to notify our close contacts that we have been a victim of a data breach and that they should double-check any communication coming from us, especially anything requesting prompt actions ─ as they could be from someone else trying to impersonate us and preying on the sense of urgency. Following on with the previous idea of what to do if we were the victim of such attacks, it is recommended to check in advance which communication channels we have at hand to reach out to our organisation about these issues. Most organisations have well-defined protocols to communicate security issues, so knowing about them will greatly reduce the time it takes us to respond and ease our mind about it.

As you see, data protection is a process to consider seriously and not only refers to the typical personal data that you can imagine. In the near future, new trends like the Internet of Behaviour (IoB) [4] will be real and a very powerful driver. Based on the collection and use of such data to drive behaviours, IOB will empower organisations for extra massive data capture actions. For instance, IOB combines technologies focused on tracking individuals such as location and facial recognition, then connects the data and maps it to behavioural events. By 2025, half the world’s population is expected to be subject to an IoB commercial or government programme.

Online resources with best practices for protecting online identity and privacy, like [5] and [6], are great to minimise our exposed data. As a rule of thumb, consider that the less data shared, the more secure one will be against data leakages, breaches and severity of attacks.

[1] https://kit.exposingtheinvisible.org/en/how/google-dorking.html[2] https://github.com/cipher387/Dorks-collections-list/

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/guides/how-to-back-up-your-computer/

[4] https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartner-top-strategic-technology-trends-for-2021

[5] https://github.com/Lissy93/personal-security-checklist

[6] https://opensourcelibs.com/libs/privacy

Are you interested in learning more about data sharing hygiene and its implications in security? Join our next CSM2021 Webinar on 21 October 2021 – 15:00-16:00 CEST. Carolina Fernández and Nil Ortiz will share techniques aiming to empower users with more tools to protect and understand their digital identity.

About the authors

Nil Ortiz (nil.ortiz@i2cat.net), Cybersecurity Innovation Expert at i2CAT, Internet Research Centre, Nil has a Computer Science Engineering degree from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and a Master’s in Cybersecurity from Camilo José Cela University (UCJC). Expert in incident response and threat intelligence, Nil has experience in multiple EU countries within multiple environments (financial, manufacture, public). He has also participated in EU H2020 Research & Innovation Projects.

Nil Ortiz (nil.ortiz@i2cat.net), Cybersecurity Innovation Expert at i2CAT, Internet Research Centre, Nil has a Computer Science Engineering degree from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and a Master’s in Cybersecurity from Camilo José Cela University (UCJC). Expert in incident response and threat intelligence, Nil has experience in multiple EU countries within multiple environments (financial, manufacture, public). He has also participated in EU H2020 Research & Innovation Projects.

Carolina Fernández (carolina.fernandez@i2cat.net) has participated in the technical implementation of 10+ research projects in multiple frameworks (FP7, H2020, GÉANT FPA) related to networking, virtualisation and security, as well as in some open calls and private projects. She has practical experience by working on the design, architecture, development, integration as well as in the operation and management of physical systems and virtual stacks. She holds a Computer Science Engineering degree from the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB, 2011). Her research interest areas include NG-SDN, NFV, OAV and the integration of the aforementioned in the security processes

Jordi Guijarro (jordi.guijarro@i2cat.net), Cybersecurity Innovation Manager at i2CAT, Internet Research Centre, Jordi has Computer Science Engineering degree from the Open University of Catalonia (UOC) and Master in ICT management from Ramon Llull University (URL). Expert in cloud and cybersecurity services, Jordi managed CERT/CSIRT teams employing proactive, reactive and value-added security services. He has also participated in EU FP7/H2020 Research & Innovation Projects and collaborates with UPC, UOC and VIU as an associate.

Shuaib Siddiqui (shuaib.siddiqui@i2cat.net), Shuaib Siddiqui has 10+ year experience working in the academic, research and industry of ICT sector. At present, he is a senior researcher at i2CAT Foundation where he is also the Area Manager for Software Networks research lab. Since he joined i2CAT Foundation in 2015, he has been active in 5G related projects (under H2020) on the topics of control, management, & orchestration platforms based on SDN/NFV, network slicing, and NFV/SDN security. He holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from Technical University of Catalonia (UPC) (Spain), M.Sc. in Communication Systems (2007) from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, and B.Sc. in Computer Engineering (2004) from King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM), Saudi Arabia.

Also this year GÉANT joins the European Cyber Security Month, with the 'Cyber Hero @ Home' campaign. Read articles from cyber security experts within our community and download resources from our awareness package on https://connect.geant.org/csm2021